The Pitts Special remains the quintessential aerobatic performer, especially in the eyes of the general public.

By Crista Worthy and Ron Chadwick

Mention aerobatics and air shows to almost anyone and the first image that comes to mind is usually a small, brightly-painted biplane—the Pitts Special.

Sure, you can do akro in an old Stearman or Waco but that means diving for enough airspeed to be able to pull the airplane through a maneuver. But with the small, lightweight, purpose-built Pitts coupled to a powerful engine, you get an aircraft that can simply power its way straight up, taking aerobatic flight to the next level.

The Pitts Special is currently built by Aviat Aircraft in Afton, Wyoming (the same factory that builds the backcountry-purposed Husky). I asked Aviat owner Stu Horn about the Pitts’ reputation for “squirrelly” handling. He replied, “The Pitts is not ‘squirrelly’ at all; in fact, it’s the opposite of ‘squirrelly’. It simply does exactly what you tell it to, immediately.”

And that is a perfect description of the airplane’s handling characteristics. This is not an airplane for sloppy pilots. It’s not a hands-off or feet-off flyer. Its short fuselage and stubby, relatively highly loaded wings give you an airplane that responds to the slightest control input, whether on or off a runway. This is an aircraft that requires you to pay attention. If you’re looking to make long cross-country flights, you’ll be exhausted hanging onto the stick all day and you’ll have to land for fuel every 90 minutes or so. But if you want to have more fun than a barrel of monkeys [ED: that’s a lot of fun…] in your local area, all the while perfecting your aerobatic skills, you can’t do better than a Pitts Special.

Although the design has been refined continuously since its first flight, current Pitts aircraft remain remarkably similar to the original. There are many variants but two main types: the S-1 (single seat) and S-2 (tandem seat).

Let’s look at the history of this remarkable airplane and then do a little hangar-flying and Q&A with Ron Chadwick, Pitts Special instructor, and aerobatic competitor.

History of the Pitts Special

Curtiss Pitts was born December 9, 1915, and grew up in Georgia. A cropduster and designer, he became inspired to build an airplane designed specifically for aerobatics. He kept his design small and light so that it would be able to perform even with a relatively small engine—just 55 hp, in fact. The airplane first flew in 1944 or 1945. Pitts experimented with monoplanes, but a biplane configuration offered the most lift and strength, along with double the aileron capability, for the small plane.

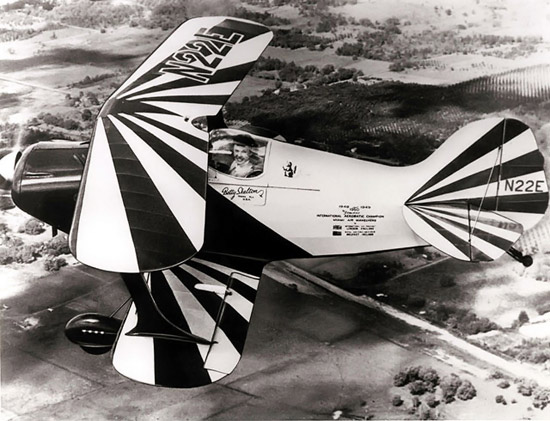

Several of the early Pitts Specials had skunks painted on them and Curtiss Pitts called them “Stinkers.” The first Pitts Special to achieve widespread fame was L’il Stinker, the second Pitts Special built, and flown to glory by aerobatics legend Betty Skelton. As told by Budd Davisson, Pitts expert, aviation writer, and friend of Curtiss Pitts, Skelton first glimpsed the airplane on the ground as she looked out of her own airplane, preparing to land for a Florida airshow. After landing, she hurried over to the little biplane, around which a crowd had gathered. She asked to sit in the cockpit, a request that was denied, no doubt due to her sex. But as soon as that airplane came up for sale, she bought it. When she brought it home, her friends and the press all witnessed her very first Pitts landing—which ended in a ground loop. But she showed them all, flying L’il Stinker to three consecutive U.S. Female Aerobatic Championships, in 1948, 1949 and 1950. (L’il Stinker now hangs in the Smithsonian.)

Pitts produced limited numbers of aircraft during the 1940s and 1950s. Homebuilders were also building aircraft from rough hand-drawn plans produced by Pitts. In 1962, professionally-drawn plans went on sale. These plans were for the S-1C, which sported a flat-bottom wing, two ailerons, a bungee-cord landing gear, and one seat.

Bessie Coleman: Early Aviation’s Barnstorming Queen

No better loved Queen in history had come from more humble beginnings than Queen Bess, the woman who changed the landscape of aviation, and race relations, in the United States, paving the path toward equality by encouraging women and minorities to pursue their dreams.

No better loved Queen in history had come from more humble beginnings than Queen Bess, the woman who changed the landscape of aviation, and race relations, in the United States, paving the path toward equality by encouraging women and minorities to pursue their dreams.

Pitts Special Two-Seat Model

As homebuilders expanded the S-1’s reputation as an excellent aerobatic aircraft, Pitts began work on a two-seat aerobatic trainer version, the S-2, which first flew in 1967 and gained its type certificate in 1971. The prototype S-2 boasted four ailerons, a symmetrical airfoil, and a 180-hp engine. The production two-seater was designated the S-2A and sported a 200-hp engine. Next to arrive was the S-2B, with better ailerons and rudder, along with 260 horses.

Pitts Special Follow-On Designs

Meanwhile, homebuilders experimented with all kinds of engines. Curtiss Pitts came out with his own variants.

The S-1D was an S-1C with a slightly stretched fuselage and four ailerons.

The S-1E was a homebuilt.

After the S-1S, Pitts designed the follow-on S-1SS.

The S-1-11B, or Model 11, was also known as the Super Stinker. This single-seater featured a 300-plus-hp Lycoming, four ailerons and a symmetrical airfoil (better for inverted flight than the flat-bottom version), and was available as either a factory-, plans-, or kit-built airplane.

The “Ultimate” version had full-width ailerons.

In 1981, the certificated, production version S-1T, replaced the S-1S.

Pitts Special Manufacturers

Factory-built aircraft were produced by the Aerotek company at Afton, Wyoming. In 1973, Aerotek began production of the single-seat S-1S. Commonly known as the “roundwing” Pitts, it featured symmetrical airfoils, four ailerons, and a different upper-wing design enabling it to stall first.

Curtiss Pitts sold the type certificates to the S-1 and S-2 to Doyle Child in 1977. Child then sold the rights to Frank Christensen in 1981. Factory-built aircraft were still built in the Afton facility, then known as Christen Industries.

In 1994, rights to the homebuilt versions of the Pitts Special were sold to Steen Aero Lab, while the Afton factory and production rights were purchased by Stu Horn of Aviat Aircraft. Aviat also owns the rights to the Christen Eagle, a biplane of similar design to the Pitts Special.

Although the Pitts Special biplane garnered the majority of aerobatic championships throughout the 1960s and 1970s, its competitive dominance began to fade with the advent of a new generation of monoplane designs from Sukhoi and Extra. And before his death in 2005 at age 89, Curtiss Pitts designed, but never built, the Model 13, an enclosed coupe. Still, the basic biplane design of the Pitts Special remains the quintessential aerobatic performer, especially in the eyes of the general public.

Current Pitts Special Models Available New

Many models and variants developed over the years are still available new, either as kits or as Aviat Aircraft factory-built airplanes. The S-2C is in production and Aviat will build the S-1S and S-1T on demand. The current production model S-2C offers increased cruise speed, more symmetrical inside and outside aerobatic handling, and better handling on landing. Aviat provides parts support for versions no longer in production; it also offers plans for the S-1S and S-1-11B. You can call them at 307-885-3151 or visit their website for more information.

The Model 12 was the last design built and flown by Curtis Pitts. This two-seat biplane, looking like a stretched Pitts, was built especially for use with the 360–400 hp Russian Vedeneyev M14P/PF radial engine. Plans are available from the current owner of the rights to the airplane, Jim Kimball Enterprises.

The Pitts Model 14 was one of Curtis Pitts’ last designs and is being developed by Steen Aero Lab and is also designed around the 400-hp Vendenyev M14PF nine-cylinder radial. Steen Aero, based in Palm Bay, Florida, also offers plans for the S-1C and S1-SS. You can call them at 321-725-4160, or visit their website for more information.

Pitts Special – Handling

I drive a Mitsubishi Evolution, a Japanese-built rally racing car. Comparing the Evo to other cars is a lot like comparing the Pitts to other airplanes. With both the Evo and the Pitts, it seems almost as if you simply think about a maneuver and the car/plane goes there instantly. This makes them easy to over-control, and there’s always a bit of a transition to a “normal” car or airplane, the controls on which will feel slow and sloppy by comparison. (Of course, the car can’t fly!) And if you’re accustomed to flying the lower-powered Citabria, Decathlon, or Stearman, the ability to power up in a vertical climb brings aerobatics into a whole new dimension.

But before you can have all that fun with your Pitts in the air, you’ve got to learn how to handle it both on the ground and in those crucial transitions: takeoff and landing. If you’re used to an Extra, Decathlon, or Citabria, you’ll find the forward visibility in a Pitts, when taxiing, is, well—awful—due to the combination of a short fuselage, small tailwheel and relatively narrow main gear. You simply cannot see straight ahead from the three-point position. So you’ll be making S-turns as you taxi.

You’ll be doing a lot of slips too, because a slip is the best way to keep the runway fully in sight as you approach to land. The airplane responds so quickly that you can maintain that slip until well into the flare and then straighten out just before touchdown. As you might suspect, this timing requires practice, so pilot proficiency requires frequent flights. But what a great excuse to go flying!

We’ve all been told to expect a go-around on every landing, but nowhere is that more true than for the Pitts Special. If it isn’t all coming together, just go around and try again. One Pitts Special owner at the towered airport where I was formally based always asked for the option instead of a full stop. He said that took the pressure off, and gave the controller the heads-up that he might go around.

And then there are the insurance premiums, which can be high because of the the type’s history of accidents or incidents that resulted from, as the NTSB puts it, “The failure of the pilot to maintain directional control during the landing rollout.” These stats are what led me to the word “squirrelly” when I spoke to Aviat’s Stu Horn. But as he and many other Pitts pilots say, the plane will simply do what you tell it to do. Just make sure you get a thorough checkout before you solo, and fly often to stay proficient.

Which leads us to instruction and our next segment: a little Pitts hangar discussion with Pitts instructor Ron Chadwick.

About Ron Chadwick

Ron Chadwick started flying at fourteen and soloed a J-5 Cub in 1964. A former Air Force fighter pilot, he flew 225 combat missions in Vietnam in the F-100. After the military, he flew for the airlines for 22 years. He also flew for several major corporations. Ron has logged over 14,000 hours in 45 different aircraft, with over 2,000 hours instructing in light, general aviation aircraft.

Ron has been flying various models of the Pitts Special since 1993 and currently competes in the “Intermediate” Category in the S-2C.

Ron is the owner and instructor at The Vertical Works flight school, based at the Scottsdale Airport (SDL) in Scottsdale, Arizona. The Vertical Works was founded to provide basic through advanced aerobatic training. Other specialties include spin training (definitely important for new Pitts pilots), formation flying, and upset recovery.

Whether the student is interested in recreational aerobatics, serious competition or just wants to have fun in a Pitts, Ron tailors programs for every schedule and budget, with a focus on building his student’s proficiency, not flight time. You can reach them by phone at 732-865-1610, email at Ron@TheVerticalWorks.com, or visit their website here.

Pardo’s Push: Amazing Piloting

It’s a story that is legendary among the fighter pilot community. Mention the name “Pardo” and a single image always comes to mind, that of a painting done by S.W. Ferguson.

The story is akin to new fighter pilots as The Very Hungry Caterpillar is to children, a sort of rite of passage, being able to recite the story in order to be inducted into the fraternity.

It was March 10th, 1967. [Click here to read more…]

About Budd Davisson

No discussion of Pitts Special instruction can be complete without mention of Budd Davisson, also of Scottsdale, and a friend of Ron’s. Budd specializes in teaching students how to land the Pitts safely. His transition course for Pitts pilots usually requires around 8–10 hours stick time for someone who already possesses a tailwheel endorsement, although actual times vary. Budd has owned and instructed in Pitts Specials for over 43 years. Out-of-town students can even stay in the private guest rooms at Budd and his wife Marlene’s expansive desert ranch house. His website is loaded with Pitts-specific information, including comparisons of the different models. You can call at 602-971-3991 or 602-971-4022, or reach him via email at BuddAirBum@cox.net.

Budd’s connection to the type, and especially its creator, is perhaps best explained in Davisson’s own words: “Curtis didn’t invent aerobatics. He didn’t invent biplanes. He didn’t invent the concept of small airplanes and big engines. He did, however, re-invent all of those factors and mold them into the image we now know as modern aerobatics. He and his little airplanes completely rewrote the aerobatic history books and, at the same time, opened the world of serious aerobatics and pure high-performance fun to the masses. It was entirely through him that an individual with dedication and a yearning for the third-dimension could take a roll of drawings and convert them into a rag and tube ball of lightning that would never fail to take their breath away. Never.”

Hangar-Flying the Pitts Special: A Conversation

Crista: With your wide experience flying different models of the Pitts Special, can you compare and contrast the handling and performance characteristics of the different models?

Ron: Most of my time has been in the two-seat models. My first Pitts was an S2A and that has a lighter control feel than the B or C. I find the B and C are pretty close control feel wise, but the three blade Hartzell prop on the C really improves the controllability at slow speeds. If you are considering competition at a regional level, the S2A should take you through Intermediate. The B and C can be competitive in Advanced but you must put in the time. At the National level only the most talented pilots can expect to be competitive with a stock-engined B or C.

Crista: Let’s talk about buying a used Pitts Special. In a way, the Pitts is about as simple as airplanes get: the airframe is fabric-covered steel tubing, you’ve got a fixed conventional landing gear, usually not much in the way of avionics or instruments, and a plywood torque box joining the wing spars. That said, given the mission of aerobatic flight, I would think that there are things you’d have to look out for: not just slop in the control systems, but you’d rather not buy one that has been pushed beyond its design envelope. For example, since the wings form one unit after they are bolted together, an impact to the lower wing could damage the upper. And the covering on any fabric airplane should be considered suspect, especially if it hasn’t been hangared. What else would you look for on a pre-buy inspection?

Ron: I am not a mechanic but the best advice I can give you is to get a mechanic with Pitts experience to do a pre-buy. That is the best money you can spend. There are a number of very qualified people around the country that you can hire. You can get on the International Aerobatic Club (IAC) explorer and locate someone near you. One of the most important things to check on a pre-buy is that all the Airworthiness Directives (ADs) have been complied with. Some ADs can cost thousands of dollars to comply with, so make sure they are all taken care of before you buy.

Crista: How much do your annuals usually run? Have you found any particular problem areas with the Pitts? I hear the tailwheel and canopy can be weak spots. (For example, the Cessna 210, the airplane I am most familiar with, is susceptible to problems with the gear doors and actuators, and the elevator has foam in it that can get saturated and cause corrosion problems.)

Ron: I have spent as little as $450 and as much as $6,000. It all depends on what the Annual uncovers and the kind of aircraft you have. There is very little about competitive aerobatics that is inexpensive and trying to “cut corners” on maintenance is a fool’s game. If you are handy, there are a lot of maintenance items that you can do yourself to try and keep the costs down. If you have a local mechanic who will come to your hangar, you can take all the panels off in preparation for the annual and put them back on when it is completed. It really helps you learn about your plane and it’s a great time to clean everything.

Crista: It’s my understanding that since there’s no floor, anything dropped will disappear and possibly jam the controls. Any advice for the owner, both on keeping control of “stuff” in the plane, and how to be sure a mechanic didn’t leave something in there?

Ron: Make sure you empty all your pockets before you get into the airplane… and your passengers too. You will not believe how much “stuff” they find in the tail of a Pitts and how quickly it will get there. One MANDATORY preflight check is to remove the seat back and, with a flashlight, check the tail for any debris. Installing clear plastic inspection covers by the elevator horn is a good idea, so you can be sure there is no debris jammed in the elevator horn.

Crista: What are your hourly operating costs?

Ron: I don’t use my Pitts on a regular basis so an hourly figure is difficult to come up with. Costs can vary greatly depending on where you live and what you fly. I fly out of Scottsdale, Arizona, so my fixed costs are probably a lot higher than some small airport in the Midwest. If you don’t consider cost of the airplane, hangar rent and insurance are generally your biggest fixed costs. Registration, airport fees, taxes, and annuals are a few more to throw into the mix. Fuel, oil, repairs, modifications and contest cost are a few more things to consider.

Lincoln J. Beachey: The Tragic Rise and Fall of the Master Birdman

Lincoln experienced phenomenal amounts of fame and recognition in his later years, but no one who knew him in childhood would have guessed. He was a small, rotund little boy, awkward and bullied by his peers. He wasn’t athletic or particularly academic, but his unstoppable passion for aviation was visible from a young age. He grew up on Mission Street in San Francisco with his older brother Hillery, close enough to ride his bike to Fillmore Hill (one of the steepest hills in San Francisco, of which there are many) and launch himself off it with no brakes, reveling in the short air-time [Click here to read more…]

Lincoln experienced phenomenal amounts of fame and recognition in his later years, but no one who knew him in childhood would have guessed. He was a small, rotund little boy, awkward and bullied by his peers. He wasn’t athletic or particularly academic, but his unstoppable passion for aviation was visible from a young age. He grew up on Mission Street in San Francisco with his older brother Hillery, close enough to ride his bike to Fillmore Hill (one of the steepest hills in San Francisco, of which there are many) and launch himself off it with no brakes, reveling in the short air-time [Click here to read more…]

Crista: Let’s talk about some mods: They include things like clear, Lexan floor panels, Haigh locking tailwheels, and replacing the bungee-cord design with a spring steel gear. Any comments on these, or others?

Ron: If you own a certified aircraft you are limited to what you can do. My best advice is to buy the best aircraft you can afford, keep it in great shape, and spend your money on learning how to fly it. I have always found it is cheaper to buy an existing higher performance aircraft than it is to modify your own aircraft.

Crista: Even though I am not short, I am short-waisted. Even with our seat fully raised, in the Cessna 210, I had to sit on a couple of towels to be able to see clearly over the cowling. If a person needs a bit of a boost in the Pitts, a pillow would compress during aerobatic maneuvers—not a good choice. I suppose you might use pieces of carpet. Do you have any other ideas for someone who needs a bit of a boost to see out the side?

Ron: You have probably heard some of the “war stories” about how hard the Pitts is to land. Those stories come mostly from people who have never landed a Pitts. One thing that will help you get the Pitts on the ground is to make sure you are sitting as high as possible in the seat. You want to get positioned in the seat so you have good visibility and can comfortably manipulate all the controls. I need to sit all the way back in the cockpit so I use a seat pack parachute. Parachutes are manufactured in several different sitting positions to fit just about everyone. Good quality seat cushions are available from many sources and you can always have a custom one made at most upholstery shops. I do not recommend towels for an aerobatic airplane.

Crista: I understand the first S-2As had a front cockpit cover that you could use to make the airplane single-place. The later design is a canopy that covers both cockpits but can fly off if not carefully latched. Any preferences?

Ron: My favorite canopy is the “racer canopy” Aviat has come out with for the B and C model Pitts. The front cover you mentioned on the Pitts S2A has a similar look as the racer canopy. The racer canopy requires some modifications to the sheet metal but allows you to change from the standard “clamshell” type to the racer very quickly. The S2A and S1T Pitts have sliding canopies and I have never heard of any of them departing the aircraft. The B and C Pitts have the clam shell type and it you forget to lock them, they will leave the aircraft.

Crista: Any clubs you recommend that Pitts Special owners join, like the EAA or International Aerobatic Club, for instance?

Ron: If this article sparks some interest in aerobatics, check out the IAC website. Contact a local chapter and see what kind of programs they have. Volunteer at a local contest; they would love to have you. If you want to compete in aerobatics you have to join the EAA and the IAC. The IAC sanctions all of the Regional contests throughout the United States. You don’t have to be a member of the IAC or EAA to attend or volunteer for a contest. A schedule of all the Regional Contests is listed on the IAC website or in the IAC magazine.

There are many schools throughout the country that offer aerobatic training in different types of aircraft. There are training camps for pilots who have their own aerobatic planes, and there are world-class instructors who will come to your area to give one-on-one training. Aerobatic training will give you more confidence and situational awareness and open up a whole new world of flying. It will make you a better pilot.

Featured Image: by Feggy Art, CC2