Preparing for your first backcountry landing, and gaining the skills to safely explore the backcountry.

This article is intended as a guide to help pilots get ready to begin thinking about landing in the backcountry and not intended to replace formal instruction from a qualified CFI.

Although a lot of the information in this article does apply to both tailwheel and tricycle landing gear aircraft, I am not going to go into tailwheel landings specifically. I think that’s a whole article all on its own.

The truth is that the backcountry is a marvelous place to operate your aircraft and well worth gaining the skills to do so safely.

We also do not (in this article) cover the topic of mountain flying, nor do we cover flying through the desert canyons or coastal ranges, etc… which a lot of backcountry/off airport operations are preceded by, so although we hope this article is helpful toward your goal of landing off field in the wild (presuming that’s your goal), it’s important to remember that there’s more to it than just the backcountry landing.

Well, I could spend the whole article just writing disclaimers and cautions, but I think you understand, so let’s get into it . . .

It’s a Good Thing You Like to Fly Because You are Gonna Need to Practice

To learn to land in the backcountry, you should practice at your home airport, and maybe a few others before attempting a backcountry landing.

The goal is simple, to sharpen your skills flying

- A standard pattern

- Stabilized approach at a given airspeed

- Landing on a point +/- a few feet

If you can’t fly a standard pattern accurately, if you can’t fly a stabilized approach at a speed of your choosing, and land at a point of your choosing in standard conditions then you are not ready to start operating in non-standard environments.

In non-standard environments, such as a mountain strip, or a dry lakebed, you will have to be able to make judgments on how to alter the standards to adapt to the demands of the non-standard environment. This intuition is only achievable from experience. For the pilot just getting into backcountry flying, you don’t have much experience in non-standard conditions and so the idea is to make up for that by being as sharp as possible in your standard flying.

When attempting to land in the wild, the stakes are high. Often no help is nearby, and even what would be a simple incident at a normal airport can be a life threatening situation in the backcountry.

Someone once said that, “Every pilot starts with a full bag of luck and an empty bag of experience. The trick is to fill the bag of experience before your bag of luck runs out.”

Backcountry Flying: Everything You Need To Know to Get Started!

There’s simply nothing else like taking off from an urban airport and flying to the mountains, ducking into a deep, twisty canyon, and plunking down onto a grass strip beside the river. You shut down, hop out, and breathe deeply after that exhilarating landing. Instead of car exhaust or smog, you smell pine needles on the brisk, clean air. The only sounds are the singing of birds and the flow of the river. In a flash, you’ve transported yourself from the stress of city life to a veritable paradise. What an accomplishment! So how do you do this backcountry-flying thing successfully? [Click to read more…]

It Starts on Downwind

Fly your downwind exactly the same way, every time. Maybe you already do this, great! Maybe you are one of those pilots whose constantly making adjustments and changing things… That’s fine too, however, I would like to begin the process of creating a pattern for yourself, a pattern that you can repeat every time with little to no variation.

Start by choosing a power setting or speed for the downwind that’s comfortable for you and fly that power setting. Yes, this means you are going to have to enter the downwind at pattern altitude and hold that altitude without ascending or descending while on the downwind unless you purposefully intend to do so. The goal is to make your downwind kinda boring, by doing as little as possible until you are abeam the “numbers” (in the backcountry these will be imaginary numbers unless it’s a really impressive backcountry strip).

When you reach the numbers make your adjustments (Prop in, cowl flaps closed, carb heat – full, throttle back, trim up etc.) almost like there was a metronome whose pace you are following: tick tock, tick tock… Methodically do things as if following the beat. Do this the same every time, slow and paced, let nothing rush you. You need to practice doing things the same every time and refining your procedures till they net predictable, consistent results.

It’s easy, even in a familiar environment, to get stressed out trying to do too many things when landing and when you get behind a little, that can escalate quickly. You can end up with your “head in the cockpit”, scrambling to catch up configuring the airplane and thus become unavailable to observe the outside environment and to make judgments configuring the airplane accordingly.

I have always thought it strange that we say we “fly” the airplane. To me the airplane “flies” itself… we observe how the airplane is flying and manage it with various adjustments. Anyway, I digress…

Doing one thing at a time, and doing those things in the same order every time, helps you to never become “rushed” or “hurried”. If you feel yourself getting behind the “eight ball” go-around. It’s a little different mindset than you might be used to, operating at a nice big paved airport with long runways… to abandon an approach if any little thing isn’t “just right” and go-around, but that’s part of the mindset of a good backcountry pilot.

The purpose of all this is to really gain that sense of expectation, to define, not just mentally, but physically to be able to recognize how “normal” feels through the various steps and stages of landing. You have to develop a kind of intuition for what “normal” is.

This intuition is what will arm you with information critical to making the kind of judgment calls you will be faced with in the wild places. Everything will feel abnormal in the backcountry, because it IS abnormal. And you are gonna work at flying your airplane in a way where things start to feel “right”, using (partly) that intuition as a guide.

We are gonna break the backcountry landing into a few parts and discuss. Those parts are: The Three Passes, The Approach, The Flare, and Touchdown.

Only the Penitent Pilot Shall – Make Three Passes

Part of the skill set of backcountry landing is flying a few passes over the airfield, dirt strip, or landing area, before deciding to attempt said landing.

I want to be as clear as I can here so keep in mind that while I will describe the following information as “three distinct passes” it’s not always necessary to do three passes and sometimes it is necessary to do four or five. The essence of flying passes is to collect information about the landing zone, and surrounding conditions. So however many passes it takes to gather the required information and feel confident is really up to you. Once again, it’s a judgment thing and every pilot will have to make their best call, for example it might be unnecessary to do a “backcountry touch and go” on a well established dirt airstrip. Conversely if you see signs of recent rain or are landing in a dry lakebed with plenty wide open space, and you wonder about the softness of the surface you will be landing on, then it becomes a VERY good idea to touch your wheels and test the surface before fully committing to the landing. Make sense? I hope so, now lets move on:

You will generally fly three distinct passes, a higher altitude pass, a mid pass and a low pass. Here are just a few of the things to look for on your various passes (I cannot list everything, obviously, so this info is just to point your mind in the right direction and maybe open your eyes to possibilities you didn’t think of):

- Pass #1

- Is this a one way airstrip?

- If I have an engine failure on a go-around or in the pattern where can I land?

- What affect will the terrain have on the winds (the wind may change direction due to valleys or cool from a river or rise from open exposed rock)

- Escape routes for a go-around

- Where is the sun? Would I be landing right into it, meaning the sun’s in my eyes?

- Pass #2

- Vehicles in the area: vehicles can enter the runway at the worst possible time for you. Spot them early and be aware of the possibilities and ready to go-around

- Campers: earthbound adventurists often do not think an airstrip is active and they will pitch a tent right on that nice flat runway

- Wildlife in the area: not just birds, but cows, deer, etc

- Obstacles: Ruts, washed out spots on the runway, muddy areas, sand, logs that Hippies may have stretched across the runway to prevent your gas burning demon from destroying natures beauty, fences, gofer holes,rocks, etc.

- Re-evaluate escape routes and take a closer look at emergency landing zones in case of engine out, or mechanical failure.

- Pass #3

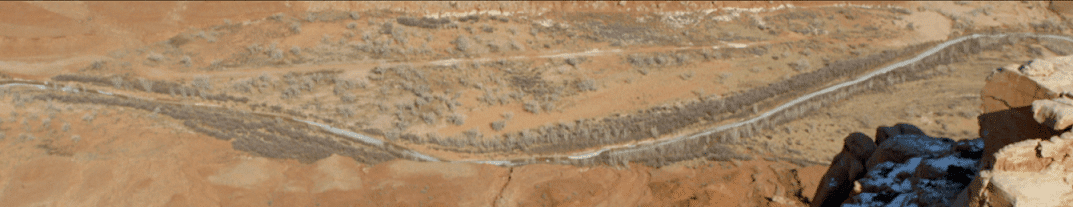

- Your low pass should be low enough that if wise, you could touch the wheels lightly on the surface without landing, testing the surface. Mud often looks dry from the air. I’ve heard this referred to as the “backcountry touch and go”. You cannot always execute this pass in confined areas. These areas are referred to as “one way” or “no go-around” strips.

- Fly your escape route: This has the benefit of giving you familiarity with the route, and terrain, should you need to fly this route in a go-around due to a balked landing or abandoned approach.

The Approach

The single most influential element of a safe successful backcountry landing lies in the approach. Now you might be tempted or you might have heard pilots say that “this is especially true in the backcountry“. Not so. Think of the difference between the backcountry and a nice paved official airport as the backcountry being less forgiving if your approach is sloppy. Thus it is the firm opinion of the editors of this site, that IF you cannot (yet) fly a comfortable, stabilized, approach and land on a point, that you cannot operate safely in the backcountry and should gain said skills before even thinking about trying to operate in the backcountry.

Most backcountry landing zones are shorter and are made of bumpy dirt, grass, sand, gravel etc (sometimes all of the above). This environment simply requires more precision and again, is less forgiving, than the standard airport environment. Whether you master and utilize “Attitude Flying” or the conventional approach is not my concern, nor do we take sides in that debate. I can name pilots who have used both techniques successfully for many years and argue fanatically for their way.

My concern and what I would drill home is the idea of preparation and practice. You should not be a brand new pilot and be reading this article thinking “I’m ready to fly off into the backcountry!“, that’s no where near true. This is intended for the experienced pilot who is new TO the backcountry and thinking of taking his/her skills to that level.

With that in mind we assume you all know how to fly a conventional approach and I am advocating that in when operating in the wild places you have a more narrow envelope of deviation that can occur in the backcountry and thus you need to clean up and perfect a certain set of skills which is primary: holding a safe, slow airspeed on approach and landing on a point.

The truth is if you can do that at 40 KIAS you can do that at 80 KIAS and all you need to make that work is more runway. Thankfully you can and should know how long your runway is. But, if you can’t yet hold an airspeed of your choosing on approach and you’re sloppy by even 5 KIAS then you HAVE a problem. You must gain the ability to comfortably fly a slow, stabilized approach (meaning your speed and glide slope cannot have unintended deviations).

It is not for me to tell you that “80 knots on downwind, 70 on base and 60 over the fence” is “best.” You have a POH for your aircraft, which has your numbers, and you need to go out at a nice safe altitude and fly mock approaches at 1.3VSO and 1.2 VSO etc.

What we are saying is that none of that matters unless you can choose an airspeed and hold it. Hold it using power, maintaining a fixed AOA, and conversely maintain the airspeed using pitch holding a fixed power setting. Practice this till you master it and can confidently configure the airplane with 10, 20, 30, 0r 40 degrees of flaps (if you have 40), choose and maintain your airspeed.

Do this on nice calm days, not windy. The reason is you need to know how what you change affects the performance of the airplane. In windy conditions it’s harder to tell what’s causing the airplane to behave the way it is mostly because everything is constantly changing in turbulent conditions.

Practice this first at “play weight” (light), then practice it some more at gross weight (heavy). The airplane feels dramatically different at gross weight. Now back to the pattern and apply your methodical standardized timing for downwind, base, and final, and adjust it as needed till you start getting predictable, comfortable results every time.

It’s not a bad idea to practice in turbulent conditions, it’s just that you need to master these skills and get a “feeling” in standard calm conditions first.

Anyway… the more precise, the more accurate you are on approach, the more calm and at ease your mind is, the more available you as the pilot are to make judgments for the non-standard conditions that ARE the backcountry, the better every other part of landing will likely be.

The Flare

In most cases these airstrips will be wider (dry lakebed such as Ibex hardpan) or narrower than your base airport. Because of this it’s easy to misjudge the height of the aircraft over the ground and begin your flare too early, or too late. Just be aware of this and remember to use your visual references (brush, trees, etc) for height estimation.

If you flare high and feel yourself sinking at an alarming rate, if you bounce or “balloon up” avoid moving the yoke forward to compensate. Use power to adjust your sink rate. If you are in a situation when you feel like moving the yoke forward, then generally, by the time you do so it’s too late and you could exacerbate the problem. Adding 100 RPM or so, to arrest a decent or reducing 100 RPM to reduce ascent is more effective and less likely to get you into trouble. If you feel out of control, GO AROUND.

Your goal is to touchdown right at your chosen point and have enough of the weight of the aircraft transferred from the wing to the wheel for effective braking as soon as possible. This doesn’t always manifest the way we want it to and so be willing and ready to make the decision to execute a go-around.

At the point the aircraft makes a slight drop to the ground, the airplane is done flying, and the pilot continues to hold the yoke back while applying brakes.

The Touchdown

This is where you want your wheels to make contact with the ground, a firm, not rough, touchdown. Your goal is to have enough of the weight of the aircraft transferred from the wing to the wheel for effective braking as soon as possible. If you hit too rough you will mechanically bounce and give up a precious braking opportunity. Conversely, gently kissing the ground with your wheels while the wing is still working also gives up braking opportunity and extends your ground roll. Some pilots will reduce flaps on the landing roll, to be sure that the aircraft is no longer flying. Whether you reduce flaps or not, your goal is to be able to brake effectively as soon as possible.

Once authority is transferred from the wing to the wheels, brake as much as possible without skidding. Remember to keep back pressure on the yoke and keep that nose wheel off the ground.

**NOTE** Prop strike concerns, or “turtling the airplane,” is really not a function of heavy braking when operating off field. Although a prop strike is more likely during heavy braking on a rough surface, that is not the primary cause of them. A prop strike is more often caused from porpoising or from holes, ditches, etc, in the surface or simply losing control and going off the runway. The idea is to coordinate as much brake as you think you can get away with, with back pressure on the control yoke to keep the nose as high as possible.

Go Arounds

When you plan to land, and something for some reason causes you to abort the landing, you execute a go-around. There are virtually an unlimited number of reasons you might choose to go-around, from too much speed to too little, too much altitude, or being too low, or seeing a couple of hikers walk out right onto the runway when you are on short final, and many more.

Always be willing to abort the landing and execute a go-around. It’s a sign of good judgment and piloting to see a pilot execute a go around when conditions are not right. Be that pilot.

Unfortunately, the go-around is a rarely practiced skill in private aviation. We have impressive aircraft with short landing ability and long runways, and since it’s sometimes seen or felt as being embarrassing to execute a go-around, we simply don’t do it. I’ve even had pilots tell me that I should discourage go-arounds in the backcountry because they can cause pilots to get into more trouble trying to execute the go-around than they would have been in just committing to the landing. The reason for this advice was simple: pilots don’t practice this maneuver and thus they often would be better off not trying it.

Well, I’m not going to discourage go-arounds in the backcountry or otherwise, in fact, it’s my opinion that you should indeed, as you have heard since your private pilot training, be willing to, and able, to execute a go-around safely. Much like everything else, it becomes something you CAN handle if you gain the skills through practice and competent instruction.

In the backcountry, you must have comfort in changing the airplane’s trajectory on approach, or in a balked landing. So once again, you practice this at your home airport until you have that confidence. A few things to consider when judging if you are “ready” when practicing. In the backcountry, unlike when you are practicing, you will most likely not intend to miss your approach or balk the landing, so you will be executing this maneuver from a place of frustration. It must be assumed that your attention will be spread thinner, and your stress levels higher when this skill is actually needed and so as you practice just keep that in mind and make sure you estimate your readiness taking this human factor into consideration.

Never land anywhere without prior knowledge of the surrounding area. This will be discussed more in the next section but the idea is to do some scouting and plan your escape routes as best you can before attempting to land. Some of this scouting SHOULD be done before you get in the airplane. Talk to pilots who have been in that area before and read up on available information about the place you intend to visit. You can’t always tell if a strip is one way from the air, and if a go-around is possible. I remember reading that a strip I wanted to fly into had no option for a go around after a certain point was reached and pilots had explained why. When I got there and flew over it I couldn’t see what they were talking about, but I trusted those reports and executed the landing accordingly believing my only option for a go-around was on approach and that once I decided to start that flare I had passed the point of no return. Once on the ground safely I could see clearly that the reports were right! I would not have known this just from observing the landing area from the air, so do your research.

The go-around is at its heart, making a choice not to land. Once this choice is made STICK WITH IT, don’t change your mind and try and land. Likewise, rule out the option of trying to salvage a landing. Get it into your head that once you decide that your approach is bad or your landing, or the general conditions in the area are bad and you make that choice to not land, don’t.

I remember I had this really exciting trip all planned out and I had friends driving out to the area (7 hour drive) to meet us there and camp together. I got to the landing area and flew my passes and flew a few more and I had this uneasy feeling about the whole situation. There were some aircraft down there already and the pilots were out watching me do my passes waiting to watch me land, as pilots do. I felt immense pressure to fight that uneasy feeling I had about my skills vs the conditions at hand, and I remember laughing out loud. My passenger inquired as to why I was laughing rather despondently and I replied, “I think Brandi and Dan are gonna be pretty pissed off at me when they get here and we went home… ”

The truth is it took some explaining because my friends are not pilots and don’t understand, and I felt stupid flying off in front of all those pilots who had landed but it was the right choice. Chances are I could have fought through that feeling and probably would not have had an incident but I had previously committed to myself that I was willing to feel stupid, and willing to face the disappointment in myself and criticism from others if conditions were not right for me to land with confidence. I knew my skills would grow in time and they did, and today those same circumstances that caused me to make that choice to not land would not deter me. However, the uneasy feeling that something was wrong and that the circumstances were out of my comfortable range of skills would cause me to abort again. I consider that a part OF the skills required to be a good backcountry pilot and I encourage you to work that onto your list of skills you practice and mentally prepare for as well.

**NOTE** If while practicing go-arounds you experience prolonged hesitation in the engine after adding power then most likely it is that your mixture isn’t set correctly. Know that it is critical that you do not have this prolonged hesitation in the backcountry and if you are not in the habit of adjusting that mixture as a part of your landing configuration, that you correct that bad habit. One sign of this (not always) is that the aircraft can backfire when the power is advanced with the mixture too lean, so if you hear a backfire (and you won’t always hear it) it could be your airplane reminding you to richen up the mixture.

**NOTE** Above I describe “prolonged hesitation” and I would also like to point out that if attempting a go-around and the aircraft does not develop full power it’s likely that the carb heat is still on, and needs to be pushed in.

**NOTE** Adding power with full flaps and a lot of trim will cause the airplane to pitch up and it can take a extreme amount of forward pressure to maintain a safe attitude. This is a part of the go-around and since you will have full flaps in on final approach in the backcountry environment, I encourage you to mentally prepare for that and pay special attention to keeping the nose from pitching up too high.

Lets talk about the aborted approach. This is done when:

- The area is unknown or confined

- One-way airstrips or no-go around airstrips

- When the pilot deems the approach to be outside of his/her intentions (too slow, too fast, too high, too low, too windy, or too little information, etc.)

Not everyone will do this but in my effort to become comfortable with the idea of committing to a landing I like to fly an aborted approach so that I can “try out” my escape route at a higher speed. It also has the benefit of allowing me to choose abort points along the approach path. These are generally visual references that help you identify the point where you can comfortably out climb terrain or obstacles.

We’ve spoken quite a bit about some things you can’t “practice” per se but rather have to mentally absorb and add to your checklist of items to apply once in the backcountry environment. I am sorry about that, I wish there were a checklist that you could follow and everything would be okay, but it’s not. You are working at becoming as prepared as possible. An informed and practiced pilot can fly into abnormal situations and that pilot can rely on experience and well honed skills to make judgement on the proper adaptation of those skills to the new circumstances. That’s kinda the deal here, you want your preparation to go to work for you, both mental and physical, so don’t discount the mental prep work. Visualize the whole experience, fly it in your mind, as well as in the airplane.

I think we have touched on the approach enough so let’s move on to a landing that goes wrong. The two most common things to happen might be bouncing the aircraft and floating. Now, I don’t want you to think that any bounce or any amount of floating is cause for a go-around, again that’s a judgment call you will have to make and practicing this at your home airport will help you be able to make those judgements. The idea is to transfer authority from the wings to the wheels for effective braking as soon as possible. It’s going to be relative to the length of runway you have to work with and several other factors.

When a go-around decision is made what you need to prioritize is first:

- Stabilizing the airplane in ground effect (control the airplane)

- Build energy in ground effect

- Change configuration and establish a positive climb

If you have done your previous passes and built your escape path by flying route before hand then this should free up your attention to focus on positive control of the airplane and less on avoiding obstacles. Again, your preparation can go to work for you but only if you did the prep work. Cutting corners could limit your options, and WILL diminish your ability to control the airplane when you need those abilities the most.

Taking Off is Often Harder than Landing

An overlooked and under discussed part of flying the backcountry is after you landed safely, had a great experience in the wilderness and are ready to depart. In most airplanes, you can land in places you cannot take off from. I find evaluation of what is needed to get airborne after I land more often kills my joy of visiting a place than whether I can land there.

When landing, all the forces are working with you (so to speak) toward your goal of getting the aircraft to the ground. When taking off, you have just about nothing going for you in that arena. It’s the airplane and the pilot vs gravity and drag.

I get some flak for the title of this section, stating that take-off is often harder than landing… Well, let me clarify what I mean: On take off the pilot has FAR less control over the outcome than on a landing. On take-off you are relying on the aircraft to overcome just about everything (gravity, drag, etc). IF something goes wrong you are often low with a nose high attitude and low airspeed, the time you have to react and the effect your reaction will have on the outcome is dramatically lower than on say approach. For me this is “harder”, harder on my stress levels, blood pressure, and so on. This means that the only reassurance you have when performing a lovely backcountry take off is your prep work. Have you really done the math? If not you may find this part of the backcountry experience pretty stressful because I can tell you that if you HAVE done all your calculations and you have a high degree of confidence that this aircraft WILL climb out over those trees given density altitude, weight, length of runway, extra drag from surface conditions, wind, etc. then you are gonna feel pretty good and take off will be much less of an issue. My experience with pilots is that they don’t do this to the extent required and kinda go by their gut more or less. Its a pain to do a thorough preflight, weight and balance, runway calculations and more, and most pilots are out of practice on this stuff. So I describe the take-off as “Often Harder” meaning often harder to do correctly/safely.

A couple of extra considerations:

You’ve been camping, so chances are, to one degree or another, you have been uncomfortable for days and the whole issue of making sure the airplane is checked out thoroughly (preflight) and that it’s balanced well, as you re-pack the gear, is much easier to cut corners on . . . and so on . . .

Commit to taking off when the air is most dense, in the early morning, or evening air. Commit to aborting a take off and how far down the runway you can be before you lose that option. I like to walk the runway with a nice camping tin full of freshly brewed coffee, and explain to it that I mean to leave and would appreciate its cooperation.

Be Wise, Know Your Limits

A wise old pilot once said to me “If you want to go fast, go slow”. Words I have never forgotten and found infinitely wise. It is possible and even way too common for pilots to venture into the backcountry without proper preparation, knowledge, or skills. While it should not be done cavalierly it all too often is and so we here echo those immortal words of wisdom.

Perhaps the best advice anyone could give is to know your limits. Don’t read this article and go off flying into the mountains to land on an access road… Get instruction, practice, prepare, gain confidence, get the endorsement of a qualified professional who has time in your aircraft type and in the backcountry. Don’t be in a hurry, take it slow and you’ll have plenty of rewarding safe experiences in the backcountry with your airplane.

Here are some more articles on flying the backcountry:

Hidden Splendor Airstrip Video

And, of course, the marquee source for information on flying the backcountry is: //www.backcountrypilot.org/