Taken Away – Working to preserve backcountry airstrips

Now I see the secret of the making of the best persons, It is to grow in the open air and to eat and sleep with the earth. ~Walt Whitman, “Song of the Open Road” (1856)

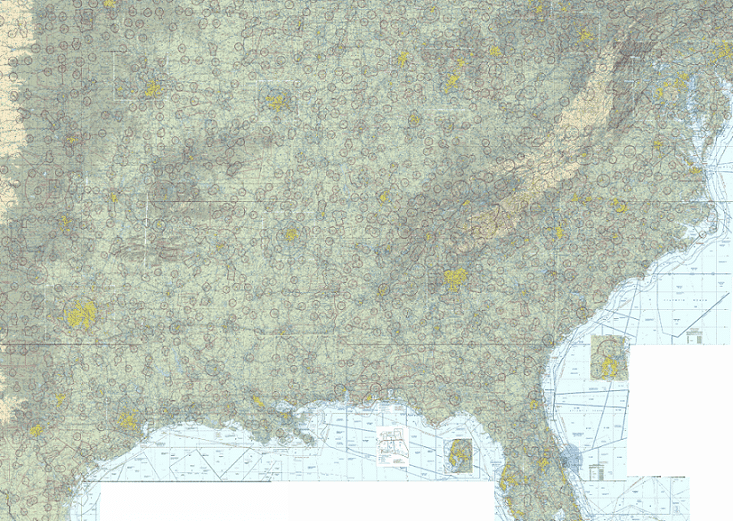

From the early days of aviation, we’ve built up a system of airports across the country, and there are now airports just about everywhere for your flying needs. I mean, have you taken a look at a sectional of the US recently, especially the Eastern states? It’s so covered in those little magenta circles, it looks like it has chicken pox.

And having access to all these airports is great for business travel, visiting friends and family, or even flying to a new destination for the ‘$100 Hamburger‘. But what if you want somewhere a little more remote? Somewhere that doesn’t have a steady flow of aerial traffic and isn’t located so close to, well, everything else. Where do you go if you want to get away from it all?

Many of you already know the answer, but for those unfamiliar with some of the more adventurous aspects of aviation, the answer is the unpaved, remote dirt airstrips of the backcountry.

Though they are somewhat rare in the Eastern, Southern, and the Midwestern United States, the Western states (in particular Utah, Colorado and Idaho) contain literally hundreds of these wonderful strips, many of them leading to spectacular and remote destinations spread across the high mountains, deep forests and sun-blasted deserts.

A Little Strip of History

So where did all these airstrips come from? Who put them there, and why? The short and obvious answer? We did, to provide easier access to these places. ‘Well duh,’ you might be saying, ‘I could have told you that. Thanks for an uninformative and frustrating answer.’ The truth is, there is a surprising lack of solid, general information about where all the airstrips came from and when. But it appears that there is a handful of culprits responsible for most of these backcountry airstrips: the US Forest Service, uranium prospectors, ranchers/homesteaders, and oil companies.

Starting in the 1920s, the US Forest Service built countless airstrips across Idaho, Oregon, Montana, Washington, Wyoming and California to help them both in their surveying and land management efforts and firefighting efforts. These strips, over the years, have experienced everything from being expanded and improved to being abandoned, forgotten and eventually rediscovered. Meanwhile, in Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Wyoming, and Nevada, oil companies started adopting airplanes as a more efficient method for surveying remote locations, building airstrips to accommodate their needs, and the Uranium Boom in the 1950s led a flood of prospectors to these states, many of whom also laid down airstrips to better facilitate their exploration and mining efforts. And mixed in among all this activity were the ranchers, many who built airstrips on or adjacent to their land for ease of access and the sake of convenience.

Now, though a broader historical overview of these strips is lacking, many of the individual strips thankfully have at least some history and information on them, and I’d like to share the stories of a few of those strips here, both to illustrate how and why these strips came about, and because I find the stories interesting (and hope you do as well.)

Chamberlain Basin Airstrip: Almost 90 Years Serving With the Forest Service

In 1906, just a year after the formation of the US Forest Service, the agency dispatched David Laing to the remote Chamberlain Basin area deep in Idaho’s backcountry to establish a management outpost. Laing had built a small log cabin by the fall of 1906, and this cabin remained in use until 1916, when the USFS contracted with nearby homesteader W.A. Stonebraker to build a larger two room log cabin. A log barn and woodshed joined the new cabin a short time later. By 1925, the US Forest Service had begun developing the land adjacent to the Chamberlain Basin Administrative Site to serve as hay and pasture land. The meadow in the basin was gradually improved and cleared during this process and began to serve as an emergency airstrip. Around 1930, with much of the additional timber cleared away through annual efforts, the strip started seeing use as a ‘fly-in’ destination for backcountry firefighting crews. Aviator Bob King1, flying either a Curtiss Robin or Fairchild monoplane is believed to be the first person to land at Chamberlain Basin.

The first official landing strip, runway 15/33 was built in 1940, and in 1941 was recorded to be 3000 feet long, and 150 feet wide. Over roughly the next decade, construction began on a second intersecting airstrip, runway 07/25. Labor was done mostly by hand, and sometime during 1952 or 53, a D-7 tractor was walked cross country out to the airstrip to level it. It was finally finished in 1954, and though the original dimensions of the runway were not recorded, one planning document makes mention of an intended length of 3400 feet.

From 1954 on, the runways saw continual use from a variety of smaller aircraft for purposes ranging from fire control to state fish and game duties to recreational use by aviators and even accommodated the needs of many larger aircraft such as DC-3s. The airstrips have been maintained, and small improvements have been introduced over time, such as in 1961, when eight sets of tie downs were added to the airstrip. A forest service inspection in 1982 revealed that runway 07/25 was 4100 feet long and 200 feet wide and that 15/33 was 2700 feet long and 120 feet wide (though subsequent inspections brought the width up to 140 feet), which was slightly more trim than its original dimensions. This inspection also revealed that the Chamberlain Basin strips now saw roughly 1000 landings per season, making it one of the most trafficked airfields in the recently established and appropriately ruggedly named Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness.

Today, the Chamberlain Basin airstrips remain a popular destination for backcountry aviation enthusiasts and continue to see consistent use from both private pilots and the Forest Service. (For a detailed, engaging write up on flying to Chamberlain Basin, Disciples of Flight’s own Jim Hoddenbach did a stellar job, available here for your reading pleasure.)

Sulphur Creek Ranch: A Mountain Retreat

In the 1930s, cattle rancher Ed Parker and his son Roy owned the Sulphur Creek Ranch and lodge. In the summers, they ran cattle and put up hay, and in the winters, they trapped and hunted animals, including valuable martens and foxes. Legend has it that Ed also had a talent for brewing moonshine, and during the prohibition, his talent was very much in demand. Ed would brew, and his son Roy would load it up, and bring it to the other ranchers and miners in the backcountry, providing them with some much appreciated ‘drought relief’.

Somewhere between 1930 and the US entry in World War 2, Sulphur Creek Ranch added an airstrip roughly 3300 feet long and 40 feet wide. During the war, the US Military put the airstrip to good use, flying in soldiers stationed at the Mountain Home Air Force Base on DC-3‘s to relax and enjoy the classic past-times of gambling, girls, and booze. Also, those pilots must have been doing some fancy flying, as the DC-3’s wingspan of 95 feet is more than twice the width of the airstrip.

In the 1950s, Idaho resident Marv Hornback purchased the ranch and lodge from the Parkers, and he and his wife Barbara turned it into a retreat for sportsmen, aviators, and backcountry enthusiasts. Today, Sulphur Creek Ranch is run in much the same manner, with most of the original buildings updated, and still in use.

Mineral Canyon: Remote and Resource Rich

In the 1940s and 50s, oil companies began surveying more remote regions in the Rockies, and Colorado Plateau area. Areas such as Mexican Mountain in the rugged San Rafael Swell of central Utah were promising candidates, and to make exploration and surveying of the area more efficient, Amoco Oil dropped a strip there in the early 1950s. The exploratory well came up dry, and Amoco capped it and moved on, leaving the airstrip behind.

However, in the 1950s, spurred on by the Cold War, a new resource suddenly came into demand: uranium. Prospectors swept into the western states, exploring the far reaches of the rugged landscapes in hopes of striking it rich with uranium ore. Because of the remote and inaccessible nature of much of the land in Colorado and Utah, many prospectors built airstrips nears claims and mines to help their exploration and mining efforts.

Spurred on by prospectors such as Charles Steen striking it rich with the ‘Mi Vida’ mine near Moab, many mining companies decided it was time to get into uranium prospecting as well. In the early 1950s, Excalibur Uranium Corporation decided to take their chances in Mineral Canyon, a remote area about 20 miles west of Moab. Surveys2 of the area by the Atomic Energy Commission indicated the presence of radioactive minerals, and so Excalibur laid down an airstrip and began exploration.

A few hundred yards northeast of the airstrip, they found uranium in the rock formations and opened a small mine. However, they were unable to extract much uranium from the area, and after a short time, Excalibur decided to close down the mine and move on. The airstrip was left behind, and quickly became a forgotten relic of the Uranium Boom as the boom came to a close in the early 1960s.

Fighting to Preserve Backcountry Airstrips

OK. Remote, high mountain strips with amazing camping, fishing and hiking? Check. Redrock desert airstrips packed with opportunities for exploration and adventure? Check. Airstrips next to beautiful backcountry ranches and lodges offering the chance for rest and relaxation in style? Check.

So, what’s the catch?

Well, sadly, many of the airstrips have not had the luck of the Chamberlain Basin or Sulphur Creek strips, with organizations and/or people taking care of them, and keeping them open to general aviation use. The Mexican Mountain airstrip, for example, fell into disrepair, shrinking from an original length of roughly 2000 feet to roughly 1300 feet as the east end of the strip was reclaimed by brush and vegetation. Additionally, the area the strip is located on was also declared a ‘Wilderness Study Area’ by the BLM, and though it technically remained available for use as it existed before the formation of the wilderness study area, there was much resistance from environmental groups to its continued use. And the Mineral Canyon airstrip, after being largely forgotten, was closed by the BLM in 1990.

And this is where the story might end for these strips, and countless others, if it weren’t for the valiant and continued efforts of many individuals and backcountry aviation organizations. Working with the BLM to produce an Environmental Impact report, the Utah Backcountry Pilot’s Association was able to show that re-opening the Mineral Canyon airstrip to backcountry aviation traffic would produce no significant impact on the surrounding land or wildlife. Then working with Mark Francis3, the owner of Aero West, the UBCP was able to eventually have the strip re-opened, and made available for public use again. The UBCP also worked closely with the BLM to have the Mexican Mountain airstrip re-opened and made available to backcountry aviators in 2008. Similar groups in other states, such as the Montana Pilot’s Association and the Idaho Aviation Association, also work to preserve backcountry airstrips.

Eventually, many of the aviators involved in the efforts to save backcountry strips realized that it was going to be necessary to work with government agencies and others on a national level to be able to affect greater change, and preserve backcountry airstrips more effectively. And so in 2003, these aviators formed the Recreational Aviation Foundation, or the RAF, with a new goal:

“Keeping the legacy of recreational aviation strong by preserving, maintaining and creating public use recreational and backcountry airstrips nationwide.”

And in the eleven years since their formation, the RAF has achieved some impressive things:

- Working with the US House of Representatives to introduce recreational aviation friendly language into the ongoing legislation.

- Helping to preserve six airstrips in the Upper Missouri Breaks National Monument area in Montana.

- Building new backcountry airstrips, such as the one at Russian Flat.

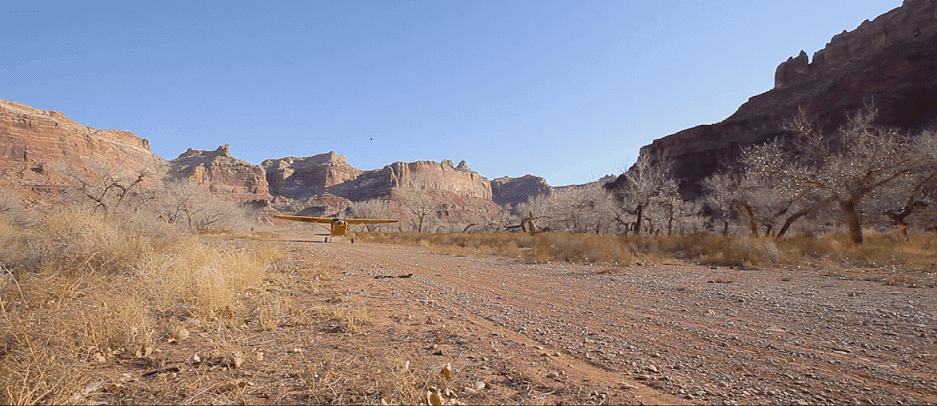

- Working with other backcountry organizations to preserve and improve existing strips in their state. Recently, this took the form of working with the UBCP to restore the Mexican Mountain airstrip to its full, original length, visible in this photo below:

At Disciples of Flight, our relationship with the RAF began two years ago, when they approached us about creating a video for them they could use to promote their cause at NBAA and other aviation related events. This video (which is viewable by clicking the ‘Play’ icon in the banner image at the top of the article) was a success, and Disciples of Flight and the RAF have continued a working relationship since then. Earlier this year, the RAF held their Redrock Round Up in St. George, where all the RAF state liaisons and interested RAF members gathered to discuss everything from the issues facing the group to sharing ideas and experiences on what’s been working in their dealings with the individual state governments. Disciples of Flight was invited to attend the Round Up and document the experience through video. We got a lot of great footage and were able to interview a lot of important aviators, including RAF founding member Chuck Jarecki and AOPA President Mark Baker. Here, for you viewing pleasure, is an exclusive video of the event:

Preserving, improving, and maintaining existing backcountry airstrips and working to build new backcountry airstrips is a noble and valuable cause. And it’s also one that requires money, time and effort. If you love flying the backcountry, please help the cause by contributing in any way you can. The RAF (http://theraf.org/) can always use, and always appreciates any and all help you can provide to preserve backcountry airstrips!

Footnotes:

1 – In 1933, at the age of 53, homesteader W.A. Stonebraker died of a heart attack at a camp 12 miles from his cabin. When his body was carried back to his cabin, it was Bob King who landed at the Stonebraker airstrip and flew W.A.’s body to nearby Grangeville, Idaho for burial.

2 – The Atomic Energy Commission conducted these surveys by flying up canyons and over formations suspected of holding precious uranium ore deposits, dragging a Geiger counter behind the plane and recording variances in the Geiger counters reading.

3 – Interesting sidenote: Mark Francis pays a yearly fee to the BLM to maintain a right of way for airplanes to use the Mineral Canyon Strip.

Sources: UBCP, The RAF, US Forest Service, Wikipedia, Bound for the Backcountry