The Sopwith Camel Would Get Fighter Pilots “A Wooden Cross, the Red Cross, or a Victoria Cross”

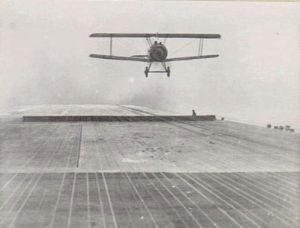

The featured image of the Sopwith Camels of the U.S. 148th American Aero Squadron at Petite Sythe (today part of Dunkirk), France, on 6 August 1918, is taken from the National Archives and is in the public domain.

The Sopwith Camel became one of the most iconic aircraft in WWI due to its well-earned reputations, both good and bad, with the pilots who flew it. Though the fighter pilots flying Sopwith Camels accounted for the most kills of any WWI aircraft (1,294 – an average of 76 kills a month for the 17 months it was in service)3, it also killed almost as many of its own pilots as the enemy did.7 Unlike its predecessor, the Sopwith Pup, or the Boeing-Stearman biplane that would come out decades later, the Sopwith Camel was not a gentle instructor, but those pilots who became proficient behind its controls were the deadliest in the skies. In fact, Canadian fighter ace Roy Brown was flying a Sopwith Camel when he credited with shooting down Manfred von Richthofen – The Red Baron.7 (Though Brown gets the credit, there is debate regarding who actually fired the shot that killed Richthofen, with many believing that it was most likely a shot fired from the ground. Not coincidentally, the Camel is also the airplane that comic strip beagle Snoopy imagines he flies when he faces off against his nemesis, the Red Baron.)

History of the Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Pup was introduced in 1916 and though it had good maneuverability and “pleasant”1 handling characteristics, it was quickly outclassed by German fighter planes like the Fokker Dr.I.2 The engineers at Sopwith Aviation Company knew they needed to build a faster, more heavily armed fighter, and soon, the Sopwith Camel was introduced to the Royal Flying Corps in 1917. At first, the Camel was known to the troops as the “Big Pup,” but quickly earned the nickname Camel because of the hump created by the metal fairings over the guns to prevent them from freezing at high altitudes.1

General Characteristics of the Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel was a single-seat biplane with staggered (upper wing forward) wings of equal area, the lower of which featured a three-degree dihedral, whereas the top had none1. It featured conventional landing gear and was constructed wood with fabric covering, with some light alloy skinning over the fuselage toward the engine4.

The original Camel was armed with two 7mm Vickers machine guns that were synchronized to fire through the propeller (a feat of engineering that is still impressive, especially given the time) and had the ability to carry up to four 25 lb (11 kg) Cooper bombs fastened on a rack underneath the fuselage.2 Other variants moved the position of the guns, some up to the wings, and experimental ground attack specific versions angled the guns downward for more effective strafing and added armor plating, but it never saw production.

Note: The specs provided are for the F.1 Sopwith Camel. 1, 4, 5

| Empty Weight | 930 lbs (421.84 kg) |

| Maximum Takeoff Weight | 1453 lbs (659 kg) |

| Fuel Capacity | 26-30 gallons |

| Wingspan | 28 ft (8.53 m) |

| Length | 18 ft 9 in (5.72 m) |

| Height | 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m) |

| Total Wing Area | 231 sq.ft. (21.46 sq.m.) |

Performance Specifications of the Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel was initially powered by a 110 horsepower (82 kW) Clerget engine but was shortly upgraded to a 130 HP (96.9 kW) Clerget 9-cylinder rotary engine connected to a wooden two-blade propeller. The Clerget engine had a tendency to choke and quit if the fuel-air mixture was not properly leaned, and being fairly tail heavy in level flight, the Camel would tend to stall and spin without power.5 Because of the Camels’ design, spins did not usually end well for the pilot.

Though there’s no specifics available regarding ground roll on takeoff and landing, warbird buffs seem to agree the takeoff distance for the Sopwith Camel to be no more than 700 or so feet, saying the WWI pilots would see a 1,000 foot-long (300 m) pasture as “the height of luxury”7. Recreations of the original Camel design can be seen in videos getting off the ground in less than that, but there’s no accounting for historical accuracy.

| Maximum Speed | 113 mph/98.2 kts (182 kmh) |

| Stall Speed | 48 mph (77 km/h) |

| Range | 300 miles (485 km) |

| Ceiling | 19,000 ft (5791.2 m) |

| Climb Rate | 1,085 ft/min (5.5 m/s) |

Handling Characteristics of the Sopwith Camel

As mentioned earlier, the handling of the Sopwith Camel was less than pleasant. The fighter pilots who flew it said that it could get you three things; a wooden cross, the Red Cross, or a Victoria Cross1. The Victoria Cross is the highest honor available in the United Kingdom, awarded for gallantry “in the face of the enemy” to members of the British armed forces. Luckily for Sopwith Camel pilots, it can be awarded posthumously.

I’m only slightly kidding. During WWI, 413 pilots died in combat, and 385 died from non-combat causes while flying a Sopwith Camel.7 The biggest detriment to its handling was its intense torque and forward center of gravity.

“In practice, the Camel proved a handful to fly, particularly with novice pilots, so much so that it gained the nasty reputation of killing off the less-than-capable aviators.”4

The Camel turned slowly to the left and put it into a nose-up attitude, which then caused sinkage and bled off the airspeed.1 Contrarily, its right-hand turns were a sight to behold. The powerful torque caused the Camel to turn right sharply, and it tended to end up in a nose-down attitude, which increased airspeed. According to some sources,1 the Sopwith Camel turned so much faster to the right that pilots who had to turn left would choose to do a 270-degree turn to the right.

However, the powerful torque created by the Clerget engine and the forward positioned center of gravity that killed off the pilots also gave them the advantage of quick, sharp right-hand turns which could prove beneficial in close-quarters dogfights.4

Variants of the F.1 Sopwith Camel

In addition to the original Sopwith Camel model, the F.1, there were five variants, including experimental models. The two most interesting and influential of which were the 2F.1 Ship Camel and the Comic Night Fighter Camel.

The 2F.1 Ship Camel

The Ship variant was designed to launch from the decks of aircraft carriers, and were modified to include a more dramatic lower-wing dihedral (5.5 degrees), floatation bags inside the rear fuselage, one of the Vickers guns replaced with an overwing Lewis gun, and a fuselage made two parts, which allowed it to be separated and stowed on a ship8. Experiments using the 2F.1 Camel as a parasite fighter were also conducted in 1918 but didn’t come to fruitition.1

The Comic Camel

The Comic night fighter variant on the Sopwith Camel was designed to defend the home front against the Germans night raids. This Camel was modified significantly. The pilot sat farther back, and the two Vickers guns were replaced with twin Lewis guns fixed to the upper wing, which could fire incendiary ammunition without blinding the pilot.

Final Thoughts on the Sopwith Camel

Unfortunately, there are only eight surviving Sopwith Camels, none of which are for sale. They cost approximately $2,300 back in 1917, and inflation skyrockets that to around $163,000.7 You could probably quintuple that to account for historical and collector value, and that might still be too low of an asking price. Companies like Airdrome Aeroplanes design kits for replica WWI aircraft, and if you’re just itching to own a Camel of your own, you can now build a very historically accurate one. The kit is available for just under $14,000 (no engine included) for those history buffs out there.

The Sopwith Camel was an intimidating airplane to many new pilots, and for very good reasons. Luckily for the Allies, it was more dangerous to their enemies than it was to their own pilots. The surviving eight remain ground-bound in rightfully earned museum displays,6 but their impact on the war effort is felt to this day. Without the Sopwith Camel and the brave pilots who managed to fly them, the world might be a very different place.

Resources and References:

1 – Sopwith Camel, Wikipedia, Retrieved 7-10-17

2 – Sopwith Camel, Ace Pilots, Retrieved 7-09-17

3 – Sopwith Camel, The Learning History Site, Retrieved 7-11-17

4 – Sopwith Camel Single-Seat Biplane Fighter Aircraft, Military Factory, Retrieved 7-10-17

5 – Sopwith Camel, Aviation History, Retrieved 7-10-17

6 – Sopwith Camel, National Naval Aviation Museum, Retrieved 7-10-17

7 – Sopwith F.1 Camel, The Aerodrome, Retrieved 7-10-17

8 – Sopwith 2F.1 Ship’s Camel, Their Flying Machines, Retrieved 7-09-17

The Life and Accomplishments of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker

The Life and Accomplishments of Captain Eddie Rickenbacker

Rickenbacker proved himself as a determined pilot, and he graduated after training for 17 days. His first assignment was as a lieutenant for the 94th Aero Squadron, a team based out of Toul, in France.

This was the very first fighter squadron that was trained by Americans, and they flew the Nieuport 28 biplane. Rickenbacker’s experience being a part of the squadron started off in a difficult manner. Most of the squadron members were graduates from Ivy League Schools, and they looked down on him.Despite the lack of acceptance [Read More]